Primary survey

The aim of the primary survey is to identify and treat immediate or imminent life threats

Introduction

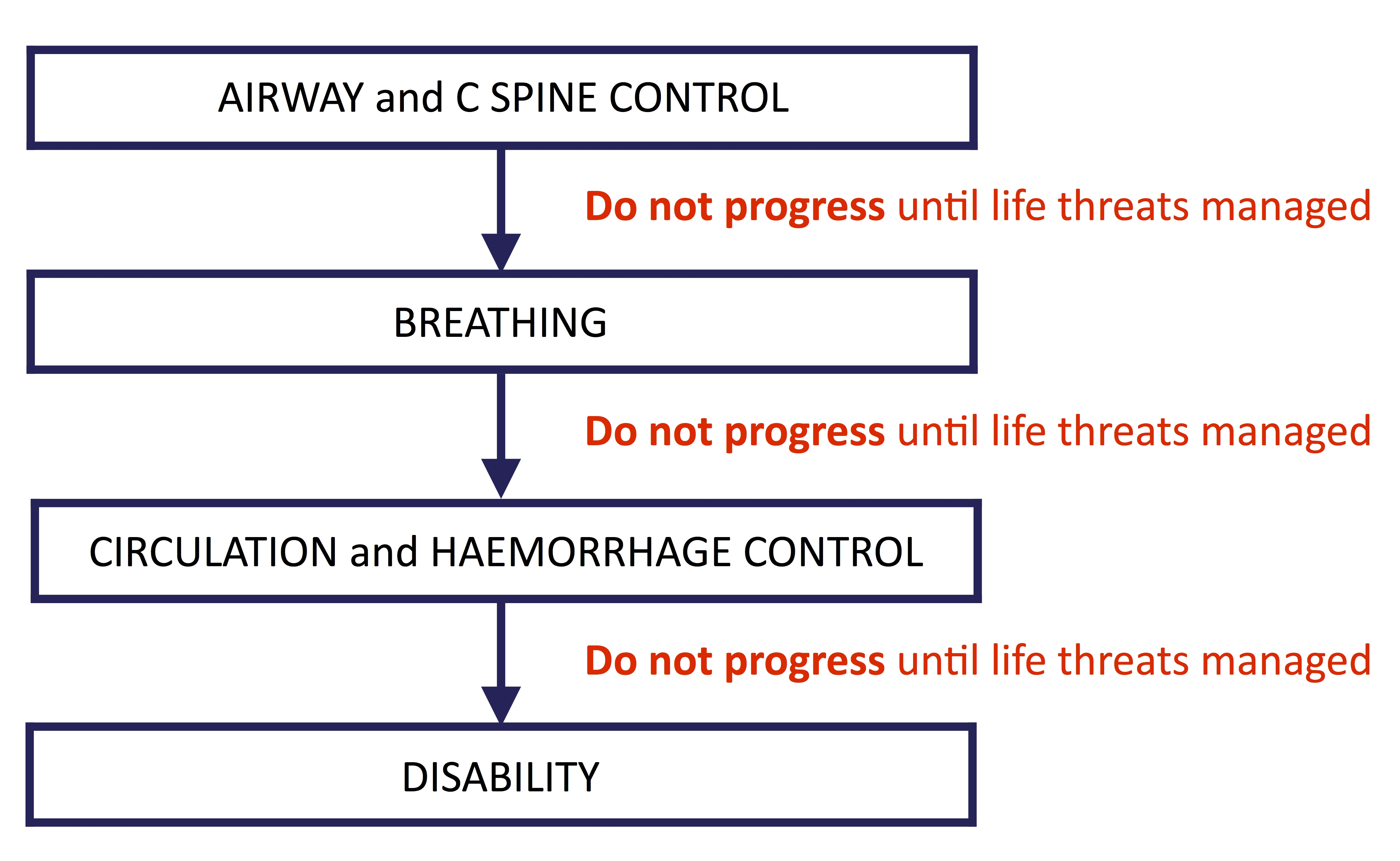

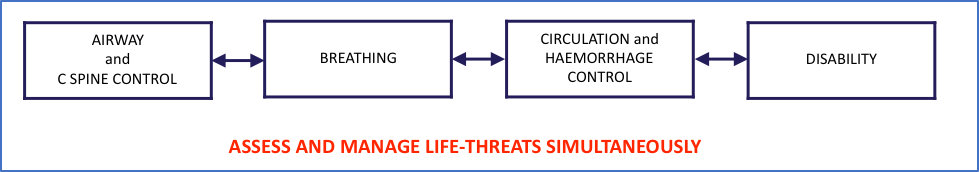

The initial management of major trauma has traditionally been taught with an “ABCDE” approach, with the aim to rule out life threats before progressing to the next step. While this might still be appropriate in settings with single physician coverage or limited resources, the primary survey is ideally achieved through parallel tasking.

Figure 1: traditional trauma management approach (would still apply for a single practitioner)

Figure 2: ideal initial trauma management team approach

After any critical intervention or if the patient destabilises – reassess systematically

Airway (with cervical spine control)

All major trauma patients should be assumed to have a spinal injury and spinal precautions should be maintained until the spine can be cleared.

Life threats

- Loss of airway patency

- Airway burns

- Facial/neck trauma

- Foreign material in airway (teeth, vomit, blood)

- Loss of airway protection

- Decreased GCS

- Respiratory/cardiac arrest

- Poor oxygenation or ventilation

- Hypoventilation with hypoxia

- Head injury

- High spinal trauma

- Severe chest trauma eg: flail chest

- Hypoventilation with hypoxia

Assessment

- Talk to the patient

- A patient that is phonating normally is unlikely to have an imminent airway risk

- Beware: dysphonia in airway burns, laryngeal injury

- A patient that is phonating normally is unlikely to have an imminent airway risk

- Inspection

- Inspect, suction

- Facial/anterior neck injuries

- Assess for signs of respiratory distress

- Tachypnoea, hypoxia, in-drawing, severe chest wall trauma

- Listen

- For stridor, snoring, gurgling

- Palpate

- Facial/mandible fractures

- Anterior neck injuries

- Subcutaneous emphysema of neck

Interventions

- Supplemental oxygen to maintain saturations >92%

- Simple airway manoeuvres

- Suction mouth

- Jaw thrust or chin lift

- Caution with chin lift: can cause movement of the cervical spine

- Place oropharyngeal or nasopharyngeal airway

- Caution with nasopharyngeal airway if possible base of skull #

- Intubation

- Indications for intubation

- Life threats (as above)

- Severe agitation

- To facilitate interventions/investigations

- Protect patient/staff

- Intractable pain

- Severe injuries

- To facilitate painful procedures

- Indications for intubation

Cervical spine control

- Maintain a neutral head position if cervical spine injury is suspected

- A hard collar can be utilised to achieve this, however there is increasing evidence that immobilisation with a hard cervical spine collar provides limited cervical spine protection from movement and can cause further injury or morbidity

CONTROVERSY: Cervical spine immobilisation

Breathing

Life threats

Assessment

- Inspection

- Movement of chest wall

- Deformity, injuries (contusions, lacerations)

- Neck veins/JVP

- Can be a difficult sign to elicit in the trauma patient (especially if hypovolaemic)

- Note vital signs

- Palpation

- Of chest wall

- Areas of pain, crepitus

- Subcutaneous emphysema

- Of trachea

- Movement from midline in tension pneumothorax or massive haemothorax

- Can be a difficult sign to elicit in the trauma patient

- Auscultation

- eFAST

- lung sliding

- fluid (blood) in hemithorax

Interventions

- Supplemental oxygen to maintain saturations >92%

- Chest decompression with thoracostomy for tension pneumothorax or massive haemothorax

CONTROVERSY: Needle vs open thoracostomy

- cover open pneumothoraces with an occlusive dressing and place a thoracostomy tube if indicated

- analgesia and ventilatory support for flail chest

Circulation with haemorrhage control

- apply direct pressure to wounds

- apply tourniquets for limb trauma with uncontrollable bleeding

- wounds may need to be packed, tamponaded (eg with a foley catheter) or sutured/stapled

Life threats

- exsanguinating external compressible haemorrhage (should be dealt with on patient arrival)

- internal non-compressible haemorrhage

- chest

- abdomen (peritoneal and retroperitoneal space)

- pelvis

- thighs (femur fractures)

- pericardial tamponade

Assessment

- Inspection

- Skin colour

- Signs of external haemorrhage

- Note vital signs

- Palpate

- Extremity temperature, capillary return, pulse quality

- Examine

- Chest, abdomen, pelvis, femurs

- Neck veins/JVP

- Can be a difficult sign to elicit in the trauma patient (especially if hypovolaemic)

- eFAST

- intraperitoneal free fluid

- cardiac tamponade

Interventions

- Arrest external haemorrhage (if not already done)

- IV access

- Insert at least two large bore (18g at least) IV cannula

- Collect trauma bloods

- FBC, UEC, LFTs/lipase, coags, ethanol level

- Venous gas and lactate

- bHCG in all women of childbearing age

- Group and crossmatch

- If IV access is not rapidly achieved

- Insert humeral or tibal IO

- Humeral IO is preferable in trauma as it allows for faster flow rates (and theoretically better if there is lower limb/pelvis/abdominal trauma with potential venous bleeding). However can be dislodged if the patient’s arm is abducted for procedures eg: thoracostomy

- Jugular, subclavian or femoral vein catherisation

- Saphenous venous cutdown (very rarely utilised)

- Insert humeral or tibal IO

- Commence IV fluid

- The use of crystalloid fluids in trauma is controversial

- It might be acceptable to infuse a small volume (eg: 250ml) of crystalloids to patients with minor haemodynamic instability with the proviso that blood products are commenced early if there is no response

- All fluids should be warmed and a rapid infuser used with massive haemorrhage

- EARLY USE OF TRANEXAMIC ACID.

- 1g of Tranexamic Acid should ideally be given within 3 hours of injury when significant haemorrhage is suspected.

- Arrange urgent thoracotomy for patients with cardiac tamponade on eFAST.

- Consider resuscitative thoracotomy for patients with thoracic trauma who are in cardiac arrest or peri-arrest

- Arrange urgent laparotomy for patients who remain unstable with free intraperitoneal fluid on eFAST

- Address suspected pelvic haemorrhage

- Place pelvic binder

- Angiography if available and indicated

- Reduce and splint femur fractures

Disability

- Assess GCS

- Assess the pupillary size and response

- Examine for lateralising signs (e.g. differing motor scores on each side) and signs of cord injury

- Blood Sugar Level

Exposure/Environmental control

- Remove clothes and expose the patient so that an adequate complete examination can be performed (should be done on patient arrival). Remove jewellery and place in patient property bag.

- Prevent the patient becoming hypothermic, measure their temperature, keep covered with a warm blanket or bair hugger.

- For patients with burns – a log roll should now be performed so an accurate TBSA% can be calculated.

Primary survey adjuncts

Analgesia

- Early pain management is essential in conjunction with on-going resuscitation.

- Opioids should be given intravenously in severe trauma

- be aware of the potential for respiratory depression and hypotension

- May require a bolus dose to effectively work in a timely fashion

- Morphine 0.1mg/kg

-

- Fentanyl 1mcg/kg

- can be more cardiovascularly protective than morphine but still take care with larger doses as per morphine

- Then titrated as per IV opiate protocol to effect

- can be more cardiovascularly protective than morphine but still take care with larger doses as per morphine

- Ketamine in aliquots of 10-20mg (adults) IV can be a useful addition to opiates for patients with severe pain

- Consider prophylactic antiemetic (ondanstron 4-8mg IV) in patients where vomiting would be detrimental eg: patients with head or spinal injuries

- Fentanyl 1mcg/kg

- Other adjuncts for pain control

- Local anaesthetics – Regional Blocks/Local Infiltration

- Consider femoral nerve blocks early for femoral fractures

- Splint fractures and reduce dislocations

- Cool burns

- Local anaesthetics – Regional Blocks/Local Infiltration

Plain film resus room radiology

The traditional “trauma series” (plain radiography) consists of a chest Xray + pelvis + lateral C spine Xray.

Due to the increased use of CT, a full trauma series might not be required.

Chest x-ray

A CXR should be performed as soon as possible in patients with suspected chest trauma based on mechanism or injury pattern.

Tension pneumothorax or massive haemothorax should be recognised and treated prior to the CXR being performed based on clinical findings. eFAST can be a useful adjunct.

Pelvis x-ray

In a shocked patient, a pelvis x-ray demonstrating a fracture can assist in determining the source of bleeding and guide treatment (see: pelvis trauma)

In patients with pelvic trauma and possible urethral injury, a pelvis x ray should be performed prior to the insertion of an IDC to rule out a fracture that may have caused a urethral laceration.

Note that patients that are awake, assessable and have no pelvic pain with a normal physical examination might not require a pelvic x-ray.

Lateral C-spine

Traditionally included in the “trauma series” but will not alter management if CT C spine is to be requested so is generally now omitted.

Selected trauma patients may not require cervical spine imaging based on validated clinical decision rules

About this guideline

First published: February 2018 (Author: Emma Batistich)

Updated April 2021 (Sue Johnson), May 2024 (Nick Longley)

Approved by: Northern Region Trauma Network, Health New Zealand | Te Whatu Ora – Northern Region, NRHL, St John

Review due: 2 years